A blog post by Derik Verkest and Bo Nash

Background

The urban environment is becoming increasingly a part of human life. It is estimated that around half of the the population lives in a city environment or a surrounding urban area. These environments themselves are an ecosystem on their own. An ecosystem dominated by a high-density of buildings, paved surfaces, and even its own climate. This climate being dominated by the Urban Heat Island. This occurs when the temperature is higher over cities than the surrounding areas. Although you would think this environment would be intriguing to study for ecologists, very little is known about urban environments and the organisms that occupy them. This understanding will become increasingly important in the coming years as it is estimated that two-thirds of the world population will be moving into this unique environment. That is what we hope to do in this lab; provide an understanding of how organisms react to being in an urban environment.

https://www.citigroup.com/citi/foundation/citi/images/Urban-Transformation-Image_lg.jpg

Introduction

This lab is going to show how human eating habits can also affect the eating habits of organisms in an urban environment. This happens because humans generate a large amount of food waste and organisms in urban environments will eat this food as it is the easiest accessible. This lab will show data indicating whether the temperature of the surface and the permeability of the surface (if water can go through it) in an urban environment will affect ant food preferences. Below you will find graphs and statistical analyses that display this information visually so you can see if an urban environment effects ant food preferences.

Methods

The procedure for sampling every year involved groups of four. Each group selected four total locations around campus, two locations that were green and two locations that were paved. Each group had a sampling kit containing a box of ziplock bags, five mason jars containing liquid food baits (water, sugar, oil, salt, and amino acid), index cards, flags, thermometer, plastic spoons, and four ant experiment signs. At each location, five cotton balls, each soaked in a unique liquid food, was placed on a labeled index card and left to sit for an hour. Group name, date, food bait, name of sampling location, and whether or not the location was green or paved was written on every index card.

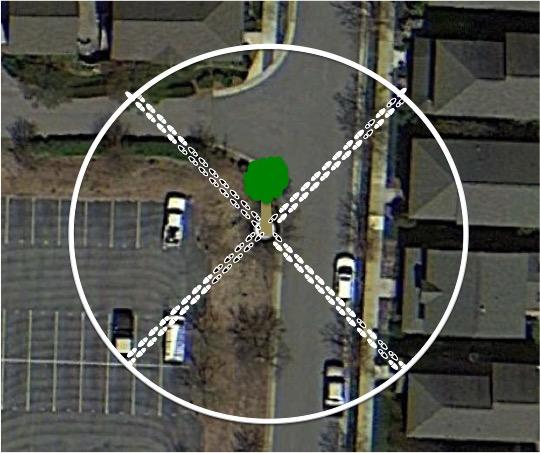

The thermometer was used to record the temperature (°C) of each sampling location, and the percent of impervious surface of the area was calculated using the Pace-to-Plant method. This method was executed by starting at the sampling location, and taking 25 steps at all four 45° angles (Fig.1). Out of all 100 steps taken, we divided the amount of steps that we took on pavement by the total of 100 steps taken to get the percent of impervious surface. After an hour, each index card, containing the food bait and ants, was put into an individual ziplock and brought back to the lab for counting.

Results

With the data acquired, we compared and analyzed the relationship between the independent variables (impervious surface percentage, temperature, food bait) and the dependent variable (number of ants) for years 2016-2018.

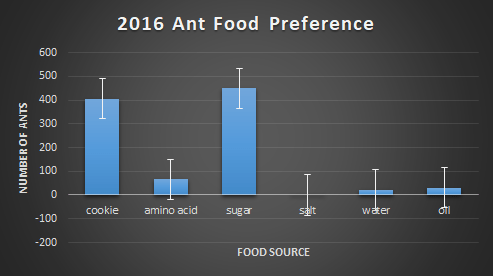

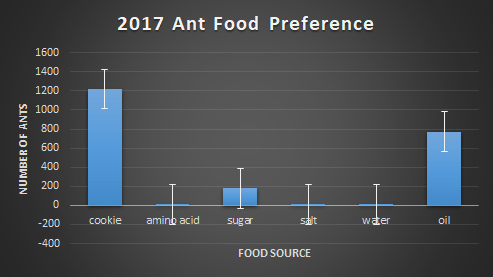

First, each food bait was compared to the amount of ants found on them. Below, figures 2-4 show this relationship. In 2016, the choice of food was overwhelmingly cookie and sugar, and for 2017 and 2018, cookie and oil were the preferred choice of food. The massive difference in ant abundance and food bait choice in 2016 is due to a drought. The lack of water would inevitability drop population numbers and emergence patterns in the ants.

Second, we ran a one-way ANOVA on food preference for each year in order to find if there was a significant preference for certain baits over others. For 2016 the p-value was 0.058, for 2017 it was 0.13, and for 2018 it was 0.051. Due to all p-values being greater than 0.05, we cannot conclude that there’s a significant difference in food preference among baits. On an ecological level, this could imply that ants are very versatile in their consumption needs, making them more adaptable to environmental change.

Finally, for each year we made two scatter plots, one assessing the affects of temperature on ant abundance and the other assessing the affects of impervious surface percentage on ant abundance. In figures 5 and 6, we see these assessments for 2016. Figure 5 shows a majority of ants being counted in temperatures ranging from 30-35°C, and figure 6 we see that areas ranging in 50-70% impervious surface area had the most ants counted.

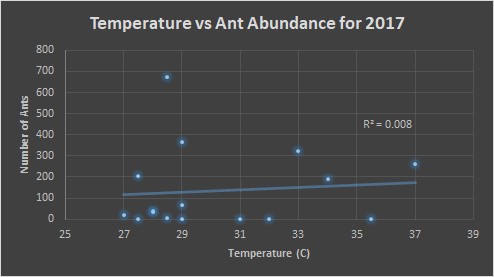

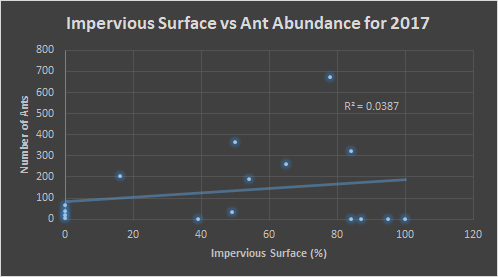

Below, in figures 7 and 8, we see the same comparisons for 2017. For the temperature, the trend indicates that the preference is similar to that of 2016, 30-35°C. However, the trend is weak. Figure 8 indicates an ant preference for impervious surface to be around 50-80% of the surrounding area.

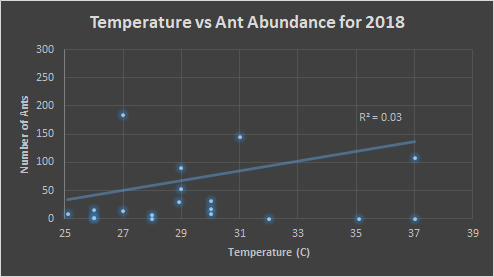

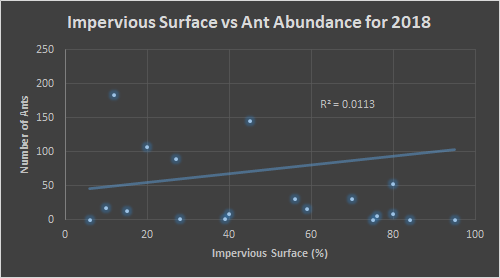

The ant abundance was also at its peak between 30-35°C for the year 2018. In order to better understand the data, a point outside the range of this graph was excluded from view, however the data point is still influencing the trend line. It was for a location where 780 ants were counted in 32°C. The same data point was removed from figure 10, where 780 ants were counted at 77% impervious surface. Here the area with 50-80% impervious surface was where a majority of ants were counted.

We see over the three years that the impervious surface percentage that produces larger ant numbers stays relatively similar, around 50-70%. This is ecologically significant because we normally think of environmental fragmentation as being a negative on animals. We might assume from this that lack of competition from other ants, due to the impervious barriers, could allow colonies to maintain a balance between population abundance and resource competition. Temperature was another factor that seemed to be important in the amount of ant activity, as all three years showed a prefer-ability for 30-35°C.

Bugs in Manhattan

A similarity between this study conducted in Manhattan and the one we performed is the impact of ants on the urban environment. In their study covering 150 blocks of street medians, ants devoured thousands of pounds of trash over the course of a year (Bakalar, 2014), which fits with the quick response time of all the ants in our study. Within just an hour, there were hundreds of ants lining up for the food we laid out.

The prosperity of these insect populations could mean that the urban space is an ideal environment for insects. With green spaces fragmented, insects compete less with one another while receiving an increase in dropped food scraps. The fragmentation can also act as an environmental barrier, like mountains do to small mammals, posing the potential to cause speciation among a parent insect species. Other organisms that may benefit from the urban environment are birds. One study looked at which birds would survive better being spontaneously place on an oceanic island, urban birds or rural birds (Møller, et al. 2015). It found that the urban birds were much more successful at establishing themselves than the rural birds were. This implies that birds born and raised in urban areas are being effected cognitively by the environment.

Humans can help improve the function of cities as ecosystems by simply being more aware and mindful of their actions. Choosing to throw your food on the grass rather than feeling morally obligated to pick up after yourself is a great start. Cities can also have regulations in place that require construction companies and developers to allocate at least 30% of the property to green space. This would ensure that urban development couldn’t over-fragment the environment to the point of mass insect extinctions.

Frontiers in Ecology: Urban Ecology

- A Multi-Trait Comparison of an Urban Plant Species Pool Reveals the Importance of Intraspecific Trait Variation and Its Influence on Distinct Functional Responses to Soil Quality: In this study the author developed an experiment that would show the change in variance of plant species as they were introduced to urban soil. The study found that the urban soil had a constricting affect on the variance and would almost filter plant variation into one specific order that had the greatest desired effect in urban soil. I found this study interesting because it explained and showed how not only does an urban environment affect plant characteristics, but the soil itself in an urban environment does so as well. As a science communicator I believe that the general public should be aware that they have a greater impact on life than they previously thought. Even the soils that humans might unknowingly create can have a drastic change on an organism’s traits. I would ask the author, if I could, how can this soil be changed to allow more variation of plant species?

- Estimating Economic and Environmental Benefits of Urban Trees in Desert Regions: In this study the authors go into detail to discuss how trees in urban areas in desert regions can not only have environmental benefits but also economics benefits as well. They found that not only did trees take away pollutants from the air, they also increased property value and decreased costs needed to cool houses. They estimated that trees saved $14 billion annually. This is important to convey to the general public because planting a tree is relatively simple and in the long run it can have really positive effects both financially and environmentally. If I had a question to the author it would be: What trees are best for the environment, and what trees are best for the economy?

Peer Review Citation

- In this peer reviewed article talks about how natural organisms outside of humans can impact urban ecology. This article in particular talks about how trees on the side of the road can decrease air pollution.

- Amorim, J., Valente, J., Cascão, P., Rodrigues, V., Pimentel, C., Miranda, A., & Borrego, C. (2013). Pedestrian Exposure to Air Pollution in Cities: Modeling the Effect of Roadside Trees. Advances in Meteorology, 2013(2013), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/964904

Works Cited

- Bakalar, N. (2014, Dec 2). Bugs in Manhattan Compete With Rats for Food Refuse. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/02/science/bugs-in-manhattan-compete-with-rats-for-food-refuse.html

- Borowy, et al. “A Multi-Trait Comparison of an Urban Plant Species Pool Reveals the Importance of Intraspecific Trait Variation and Its Influence on District Functional Responses to Soil Quality.” Frontiers, Frontiers, 2 Mar. 2020, doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00068

- Isaifan, et al. “Estimating Economic and Environmental Benefits of Urban Trees in Desert Regions.” Frontiers, Frontiers, 21 Jan. 2020, doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00016

- Møller, A., Díaz, M., Flensted-Jensen, E., Grim, T., Ibáñez-Álamo, J., Jokimäki, J., … Tryjanowski, P. (2015). Urbanized birds have superior establishment success in novel environments. Oecologia, 178(3), 943–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-015-3268-8

Credit

- Bo Nash: Introduction, Background, Frontiers in Ecology, Peer Review Citation

- Derik Verkest: Results, all graphs, Bugs in Manhattan